The final say

News

Must read

Families refusing access to support

Features Test

Producing robust capacity assessments and the approaches to assessing capacity

Disability discrimination and proportionality in housing management

Cross-border deprivation of liberty

Dealing with unexplained deaths and inquests

Court of Protection case update: May 2025

Features

Producing robust capacity assessments and the approaches to assessing capacity

Disability discrimination and proportionality in housing management

Cross-border deprivation of liberty

Dealing with unexplained deaths and inquests

Court of Protection case update: May 2025

Sponsored articles

What is the role of the National Trading Standards Estate & Letting Agency Team in assisting enforcement authorities?

Webinars

Is Omeprazole the new EDS?

More features

Provision of same-sex intimate care

Court of Protection case update: April 2025

High Court guidance on Article 3 engagement in care at home cases

‘Stitch’, capacity and complexity

Issuing proceedings in best interests cases

Court of Protection case law update: March 2025

The Health and Social Care (Wales) Bill Series – Regulation and Inspection of Social Care

The Health and Social Care (Wales) Bill Series – Direct Payments for NHS Continuing Healthcare

What is the right approach to Care Act assessments?

Disabled people in immigration bail: the duties of the Home Office and local authorities

Capacity, insight and professional cultures

Court of Protection update: February 2025

Setting care home fees

Could this be the end for local authority-provided residential care?

“On a DoLS”

It’s all about the care plan

Court of Protection case update: January 2025

Mental capacity and expert evidence

Best interests, wishes and feelings

Capacity, sexual relations and public protection – another go-round before the Court of Appeal

Court of Protection Update - December 2024

Fluctuating capacity, the “longitudinal approach” and practical dilemmas

Capacity and civil proceedings

Recovering adult social care charges via insolvency administration orders

Court of Protection case update: October 2024

Communication with protected parties in legal proceedings

The way forward for CQC – something old, something new….

The Ombudsman, DoLS and triaging – asking the impossible?

Outsourcing and the Human Rights Act 1998 – the consequences

Commissioning care and support in Wales: new code of practice

LGA warns councils and housing associations on equalities laws compliance

- Details

The Local Government Association has warned councils and housing associations considering changing services or altering their housing allocation policies to ensure they comply with the Equality Act.

The LGA said: “Changes to housing allocation plans that have the net effect of negatively impacting on those with protected characteristics, such as disability, race or age, may well be against equality laws, and would be subject to a legal challenge.”

The Association added that – in addition to housing – other policies such as schooling and public health outcomes would need to be actively considered when delivering more “locally driven” services.

“It is clear that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to services will no longer be enough to be compliant with the rules around promoting equality,” it said.

The warnings came as the Association published two sets of guidelines aimed at helping local authorities and other bodies meet their equalities obligations. These are:

- The Social Housing Equality Framework: these guidelines have been designed to help councils and housing associations ensure appropriate housing is provided to vulnerable people. They have been revised to take into account changes to equality legislation, as well as to the regulatory and inspection regimes for the social housing sector. The SHEF also reflects the greater freedom in relation to allocations.

- The Equality Framework for Local Government: this is intended to help councils “to continue to consider the impact that their policies on areas such as education have on the people who live and work in their area, and meet their wider requirements under equalities legislation”.

The LGA highlighted how councils can request a peer review and challenge to ensure that they meet the requirements of the SHEF guidance. “If a peer review team agrees that the required level has been met, then the council will be awarded a SHEF recognition award,” it said.

Cllr David Sparks, Vice Chairman of the LGA, said: “The equality frameworks can help ensure that councils not only provide high quality local services, but also ensure that local people are placed at the centre of decision making.

“Public bodies are rightfully bound by provisions within equalities legislation and local government wants to avoid legal challenges and protect the needs of vulnerable people. I urge councils to use the frameworks as a tool to promote equality and assist with compliance to the law.”

The LGA plans to launch a third equality framework, relating to fire and rescue, in March.

For more information, go to www.local.gov.uk or contact

An age-old question

- Details

Conducting age assessments is often a challenging task for local authority children's services teams. Sally Gore reviews recent developments in the case law.

Children’s Services departments are often called upon to assess the age of a young person seeking support under the Children Act 1989. Such cases commonly involve young unaccompanied asylum seekers who have no recourse to public funds save for any entitlement they may have by virtue of being a child in need, as defined in s.17(10) Children Act 1989. This support may include not only support and maintenance under s.17 but also accommodation under s.20, Children Act. For young people who are in receipt of such accommodation for a prescribed period, there is, in due course, access to ‘leaving care’ support.

Consequently, if an individual is able to establish that they are a child at the point at which they present themselves to a local authority and request assistance, they can look forward to significant and far-reaching support for a considerable period of time. The decision as to a person’s age also has implications for the education they receive in this country and for decisions that may be taken in the future by the immigration authorities.

Guidance

For a number of years now, the guidance for the conduct of age assessments has primarily come from the case of in R(B) v Merton London Borough Council [2003] EWHC 1689 (Admin), [2003] 2 FLR 888. Stanley Burnton J set out the following principles to be followed by local authorities:

- Avoid judicialisation of the process. Age assessments in borderline cases are complex but should not be approached like a trial.

- The assessor should explain to the subject of the assessment the purpose of the interview.

- Except in obvious cases, a person’s age should not be assessed based on appearance alone.

- If there is reason to doubt what a person says about their age, the decision-maker will need to ask questions designed to test credibility.

- The subject of the assessment does not bear the burden of proving their age.

- A local authority must conduct their own assessment of a person’s age. It is not enough to simply adopt a decision made by the Home Office.

- If the assessors disbelieve the subject’s assertion of their age, they must give adequate reasons for their decision. However, they are not required to give detailed reasons such as would be required in other contexts.

- If an interpreter is required, it is best practice for them to be physically present at the interview rather than available by telephone. Interpreters should also make a note of the questions asked and the answers given.

- The law does not require a verbatim note of the interview but it is best practice to keep such a note.

- The assessor must be mindful of his or her lack of familiarity with the subject’s background.

- If there are matters that the assessors feel point towards an adverse decision, they must explain this to the subject of the assessment and give them the opportunity to comment.

The London Boroughs of Croydon and Hillingdon, whose locations mean that they encounter more of these cases than many others, have also drawn up their own guidance. Practice Guidelines for Age Assessment of Young Unaccompanied Asylum Seekers provides best practice guidance to social workers conducting age assessments. These guidelines were approved by Stanley Burnton J in R(B) v Merton London Borough Council (above).

A New Approach to Age Assessment Cases

In 2009, a decision of the Supreme Court fundamentally altered the way in which disputed age assessments are challenged in the courts. Although a challenge is still brought as a judicial review, following R(A) v London Borough of Croydon; R(M) v London Borough of Lambeth [2009] UKSC 8; [2010] 1 All ER 469, the court may need to conduct a full trial of the issue with oral evidence from the parties.

The rationale for this is that a person’s age is an objective question of precedent fact. It is not something that can be evaluatively assessed by a local authority in the way that the question of whether someone is ‘in need’ or lacks ‘suitable accommodation’ is a matter of evaluative judgment. Consequently, a challenge to a decision based on a disputed age assessment should not be challenged by way of a conventional judicial review in the way that evaluative questions are challenged; rather, the court should determine the subject’s age on the basis of evidence.

Following this decision, further guidance on the conduct of fact-finding hearings was given by Holman J, giving directions in six age assessment cases that had been awaiting the decision of the Supreme Court.[1] This guidance dealt with the procedural and case-management issues that arise from the new approach to disputed age assessment cases:

- A claimant wishing to challenge a decision that is based on an assessment of their age must still apply for permission as would be required for any other judicial review.

- The court must do more than determine whether or not a claimant is a child; it must make its own decision as to the person’s age based on the evidence.

- The standard of proof is the ordinary civil standard.

- The local authority social worker(s) who conducted the assessment would normally be expected to give oral evidence.

- The claimant would also be expected to give evidence. The case law on children giving evidence in care proceedings is not directly relevant to this type of case.

- Although earlier cases had highlighted the potential pitfalls of relying on medical evidence of a person’s age, a medical report should not be entirely disregarded either by a local authority conducting an assessment of age or by a court hearing a challenge to such an assessment.

Burden of Proof

The issue of which side should bear the burden of proof in these hearings has been raised in a number of recent cases. In R(F) v Lewisham; R(D) v Manchester (above), Holman J suggested that the burden of proof is not necessarily borne by the claimant. This will depend on the circumstances of an individual case and so is a matter best left to the trial judge.

In a later case, Langstaff J pointed out that the decision facing the Court is not simply one of choosing between two alternatives.[2] Rather, the parties’ respective positions on the claimant’s age may represent opposite ends of a range of possible ages, and it is for the Court to decide where within that range the claimant’s true age falls as a matter of fact.

More recently, in R(CJ by his litgation friend) v Cardiff City Council [2011] EWCA Civ 159, the Court of Appeal held that in the context of determining whether or not a claimant was a child, the Court below had been wrong to approach the question in terms of the claimant needing to discharge the burden of proof. A person’s age is a question of precedent fact that determines whether or not a public body has a power to act (in this case, exercise the powers under Part III, Children Act). It is not for a public body to determine its own jurisdiction. Therefore, in this situation, there should be no legal hurdle that a claimant needs to overcome; it is simply for the Court to decide, on the balance of probabilities, whether the claimant is/was a child at the relevant date. For the same reason, there is no requirement to give a claimant the ‘benefit of the doubt’.

Administrative Court v Upper Tribunal

Although a claim in an age assessment case may be commenced in the Administrative Court, if permission is granted, the case will now usually be transferred to the Upper Tribunal Immigration and Asylum Chamber. This is in accordance with s. 31A(3), Senior Courts Act 1981 and Article 11(c)(ii) of the First-tier Tribunal and Upper Tribunal (Chambers) Order. The test for determining whether to order a transfer is whether "it appears to the High Court to be just and convenient" to make the transfer. This test will usually be satisfied because the Administrative Court does not generally decide questions of fact on contested oral evidence and the Upper Tribunal is already experienced in age assessment of children from overseas in the context of disputed asylum claims. The law and procedure that applies in the Upper Tribunal is the same as that applicable to age assessment cases that would previously have been heard in the Administrative Court.

Expert evidence

In R(AS) v London Borough of Croydon [2011] EWHC 2091 (Admin) at [27], His Honour Judge Anthony Thornton QC (sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge) gave the following guidance in relation to the use of expert evidence in these cases:

“The Administrative Court or the Upper Tribunal should limit the number of expert witnesses that are permitted and should follow the practice provided for in the CPR 35, including the proposed changes in practice to be introduced by amendment in 2012, relating to defining the issues to be addressed, the number and disciplines of experts to be permitted and the use, wherever possible, of jointly instructed experts. However, experts' meetings and a joint statement prepared by experts of similar disciplines will not usually be ordered. The appropriate directions for expert evidence should be sought from the Administrative Court (or the Upper Tribunal in a case referred to or started in that tribunal) and issued by the court or tribunal prior to the hearing of the substantive dispute”.

Settlement

In the event that a disputed age assessment case settles before a final hearing, the parties are required to submit the proposed settlement to court, with an agreed statement of reasons, for the Court to approve the settlement.[3] This is because the child claimant is a protected party and CPR 21.10 provides that no settlement, compromise or payment shall be valid without the approval of the court.

A right ‘in rem’

A declaration of a person’s age by a Court in a disputed age case is a declaration ‘in rem’.[4] That is, it is a declaration that nobody can go behind. It binds not only those parties to the proceedings but also anyone with an interest in the claimant’s true age.

Sally Gore is a barrister at 14 Gray's Inn Square. She is the author of The Children Act 1989: Local authority support for Children and Families, which is published by Jordan Publishing.

[1] R(F) v Lewisham London Borough Council; R(D) v Manchester City Council [2009] EWHC 3542 (Admin), [2010] 1 FLR 1463.

[2] MC v Liverpool City Council [2010] EWHC 2211 (Admin); [2011] 1 FLR 728.

[3] R(AS) v London Borough of Croydon (above) at [38].

[4] R(AS) v London Borough of Croydon (above).

Supreme Court starts hearing "biggest community care case in 15 years"

- Details

The Supreme Court is this week hearing a landmark case on the extent to which a local authority is able to take its financial resources into account when meeting assessed needs for social care.

In a case described by the claimant’s lawyer as potentially the biggest in community care for 15 years, the seven justices will also consider the use of Resource Allocation Schemes (RAS) by local authorities.

The case is being brought on behalf of KM, a 26-year-old man with a range of serious physical and mental disabilities.

To work out the appropriate payment in his case, Cambridgeshire County Council – the local authority responsible for his care – applied an RAS, a tool that calculates funding in respect of needs based on the average funding made available to those with particular needs in the local authority area.

The council also made additional funding available through an Upper Banding Calculator, which it uses in severe cases such as this.

Cambridgeshire calculated the direct payment required to provide for KM’s assessed needs as £84,678 a year.

An independent social worker had also assessed KM’s needs – an assessment that the council agreed with – but estimated that the annual cost of supporting him was in fact £157,060.

His mother argued that the amount proposed by Cambridgeshire was insufficient and had been irrationally arrived at.

The local authority won the case in the Court of Appeal in June 2011. Sir Anthony May, President of the Queen’s Bench Division, said the judges were sympathetic to the claimant’s submission that Cambridgeshire did not give adequate reasons “since the process by which they eventually arrived at an intelligible explanation of the £84,678 was….tortuous”.

However, Sir Anthony went on to say that an intelligible eventual explanation was given (on 3 June 2010) and that this explanation was rational. The Court said there did not need to be a “finite absolute mathematical link” between the needs and the assessed direct payments.

The judge also said that local authorities “whose funds are not limitless, are both entitled and obliged to moderate the assessed needs to take account of the relative severity of all those with community care needs in their area”.

The key issues being considered by the Supreme Court in KM are:

- Whether the House of Lords ruling in R v Gloucestershire CC ex p Barry [1997] AC 584 – permitting local authorities to take their resources into account – was correctly decided and, in consequence, whether Resource Allocation Schemes are a legitimate means for local authorities to apply to determine funding to be made available to persons in need by means of ‘direct payment’?

- If Barry was correctly decided, and Resource Allocation Schemes acceptable, what level of explanation must the local authority provide of the sum awarded and whether sufficient reasons were given in the case of KM?

- Whether Cambridgeshire’s decision in this case was irrational because the amount awarded was manifestly insufficient to meet the appellant’s assessed eligible needs?

The claimant’s appeal to the Supreme Court has been backed by four national charities: Sense, Guide Dogs, the National Autistic Society, and RNIB.

The charities want Barry to be overturned, arguing that each individual should be assessed in the first instance in terms of what care they need, rather than the local authority’s financial position.

Irwin Mitchell, KM’s lawyers, said that if the appeal were to be successful, it would mean that every local authority in England and Wales would have to reconsider how it assessed the needs of disabled people.

The Secretary of State for Health, Andrew Lansley, has intervened in the case.

Alex Rook, from the Public Law team at Irwin Mitchell, said: “This is potentially the biggest community care case for 15 years. The court will hear submissions on behalf of the national charities that they seek to end the inequity of the current situation and determine once and for all that care needs are care needs regardless of the local authority in question. Each of the charities firmly believe that a person’s individual needs are the same regardless of whether they live in Hackney or Harrogate.

“Our clients have long campaigned to ensure there is complete transparency in terms of what an individual’s care needs are. Despite the difficult current economic climate, this should not mean that people miss out on the crucial social care they need.”

Costing the deprivation of liberty safeguards

- Details

One of the criticisms that are frequently levied against the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) is that they are enormously expensive. However, there appears to be no official data on how much they are actually costing in contrast with predictions, and so it is hard to know whether this criticism is fair, writes Lucy Series

Several rulings on the scope of Article 5 (and hence the DoLS) have mentioned the wider resource implications of finding that a particular situation amounts to a deprivation of liberty (e.g. Re RK [2011] [8], [44], [45]; P & Q v Surrey County Council [2011] [4] –[5]). And many of these deprivation of liberty hearings are currently being heard in the High Court; a function which they have been allocated no additional resources for. It seems likely that this additional workload must have knock-on consequences for the ordinary family law work of the court, and I expect the courts must be feeling the strain.

Because of the dearth of official data on the cost of the DoLS, I have tried to put together some costings on the legal process. And what I found is not pretty at all. The headline is this: even though the number of applications are far lower than anticipated, even though the proportion of those appealing is far lower than anticipated, the cost of the DoLS is ballooning far beyond the predictions of the impact assessment. Furthermore, whereas the impact assessment anticipated that the number of applications, authorisations and appeals would decrease after the first year, all the evidence is that applications and appeals - and their associated costs - will continue to rise. If these estimates are correct then the overall cost to the public purse could be very significant indeed.

The danger is that this will act as a disincentive for supervisory bodies to help detainees exercise their rights of review.

The cost of the assessment process at local level

Shah and colleagues have shown that the cost of the assessment process under the deprivation of liberty safeguards far exceeds the predictions of the impact assessment (SHAH, A., PENNINGTON, M., HEGINBOTHAM, C. & DONALDSON, C. (2011) 'Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards in England: implementation costs'. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(3), 232-238).

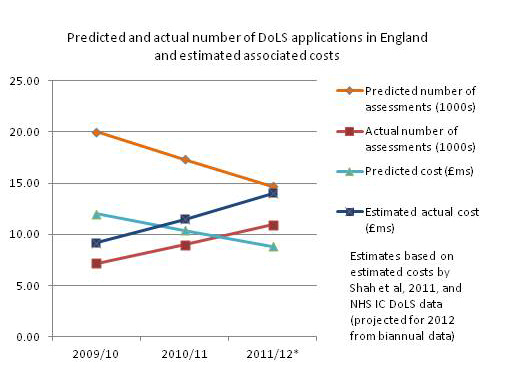

They found that whereas the impact assessment catered for 20,000 assessments for DoLS (in England, another 1000 in Wales) at a cost of £600 per assessment, it was in fact costing around £1277 per assessment. However, the authors concluded that the budget allocated for assessments is likely to be adequate because the number of applications has been so low. But since they wrote, the number of applications - and hence assessments - has been rising. If Shah’s estimates are applied to the more recent DoLS annual statistics, and extrapolated out from the data for 2011-12 so far, we can see that the cost of assessments now far exceeds predictions. Contrary to a projected year-on-year decrease in the use of the DoLS, the number of applications – and associated costs - may continue to rise.

If this is how much more applications and assessments are costing - what about the cost of the legal process?

The impact assessment predicted that 25% of all DoLS applications would result in authorisation (5250 for the first year); that 25% of authorised cases (approx 1313) would result in a request for legal advice funded by the Legal Services Commission (LSC), and that 2.5% of all DoLS authorisation would result in an appeal (approx 131 per annum). The number of applications, authorisations and appeals was predicted to fall year on year, and reach a steady-state in 2014/15. They estimated the typical cost of a legal aid certificate for advice to be £141, and the typical legal costs of a DoLS appeal – including legal aid and court costs – to be £9k. It is unclear from these estimates whether they also factored in the legal costs to supervisory bodies of appeals.

What are appeals actually costing under the DoLS?

Last year I asked the LSC for the costs of closed legal aid certificates for advice on s21A MCA; the average cost was £388.54 (2.75x greater than predicted). The average cost of a legal aid certificate for legal representation was £10,993.30; so already the cost of representation for a single litigant is greater than the total £9k predicted by the impact assessment for the total legal costs of an appeal. It would normally be anticipated that at least two legal aid certificates would be issued for a s21A appeal: one for P and one for P’s representative or another family member involved in a dispute (bringing the total legal aid cost to £21,987).

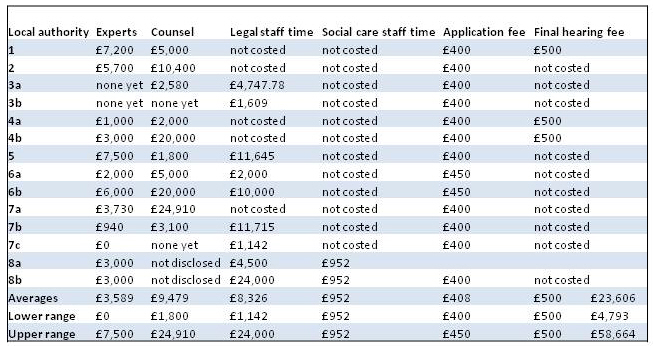

I have also obtained estimates of cost breakdowns from solicitors; however the cost estimates of the two solicitors I asked were much higher than the legal aid certificates, ranging around £12-23k per client. I assume this may refer to privately funded litigants, where solicitors’ fees may be higher – so I have not based the following calculations on data from solicitors, only from local authorities. I also asked local authorities to give me estimates of how much appeals were costing them. I have heard back from only a few, but here is a table of the costs they cited:

Click on graphic to enlarge (opens in new window)

Some local authorities estimated a range for individual costs, so I put an entry into this table for a case at the upper and lower range for that local authority (e.g. 3a, and 3b are the upper and lower range estimated by local authority 3). Others cited the costs of particular cases, some still ongoing, so those estimates have a line each. Some costs were only provided by some local authorities - very few quantified the costs to their in-house legal staff and DoLS teams. I took an average for the costs of experts, counsel, legal staff, DoLS staff, and court fees, and summed them to produce an average estimated cost of a DoLS hearing for a local authority: £23.6k (range: £4.8k-£59k).

To produce an estimate of the overall cost to the public purse of a single hearing in the Court of Protection about a deprivation of liberty, I assumed that it would involve two legally aided litigants (P, and P's representative) and a supervisory body. Often a managing authority would be listed as a defendant as well, but I have not considered these costs as they will not usually be met from the public purse (not directly, at least).

One local authority commented that there were also cases where a health authority might be listed as well, if they were funding the care home fees - I have not included such eventualities in my estimates. Neither have I been able to consider the Office of the Official Solicitor for their time, as no such data is collected. In short, the estimates I am basing the following projections on are likely to be very conservative. Based on these assumptions, a conservative estimate of the typical cost of a DoLS hearing to the public purse would be £45.6k, not £9k, as anticipated by the impact assessment.

Factoring in the actual number of appeals

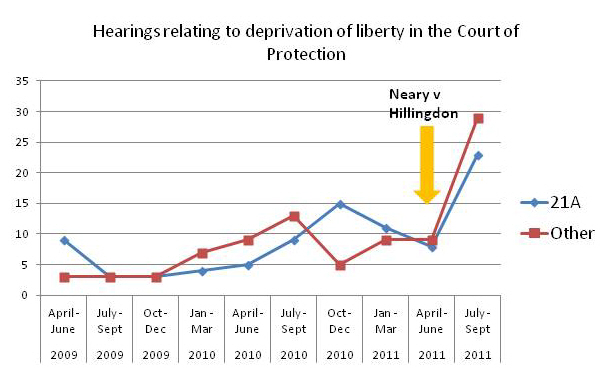

Fortunately for the public purse, although not for detainees, the DoLS ‘have barely begun to function’ (Mental Health Alliance, 2010). The impact assessment predicted 2.5% of all authorisation would result in an appeal under s21A Mental Capacity Act. In the first year, there were only 19 appeals under s21A (0.56% of all authorisations); in the second year there were 40 (1.52% of all authorisations). However, following the case London Borough of Hillingdon v Neary [2011] there is a visible ‘spike’ in appeals under s21A as well as court hearings relating to deprivation of liberty under other parts of the MCA:

Click on graphic to enlarge (opens in new window)

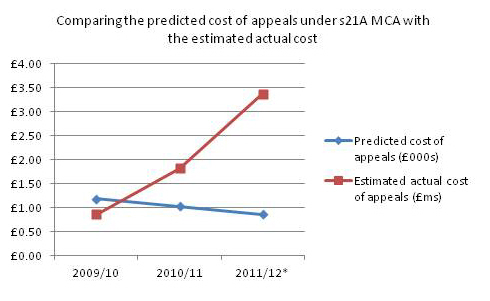

If we factor in the estimated average cost of a s21A MCA appeal, with the actual number of appeals, and compare it with the impact assessment predictions, it may look something like this:

[* Estimates for this financial year extrapolated out from data on appeals to October 2011]

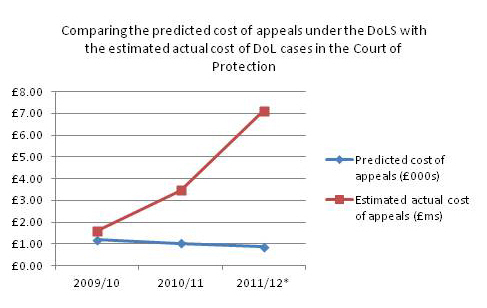

But of course, what the impact assessment did not take into account was that a large number of cases in the Court of Protection relating to deprivation of liberty (in fact, the majority) are not brought under s21A MCA. This is because they are either cases where a public authority has had to seek authorisation directly from the court, and annual reviews, because the DoLS did not take into account the full range of contexts where a person might be deprived of liberty (a rather costly oversight, it would now seem).

Or they are cases where, for one reason or another either P or P's representative has been unable to trigger a s21A MCA appeal, but there is an ongoing dispute. And so, following Neary, supervisory bodies are acting on advice to refer disputes involving deprivation of liberty to the Court of Protection themselves where the appeal process has failed. They may well do so under s15 and/or s16 MCA. So, taking into account these cases as well, the costs of all cases in the Court of Protection concerning deprivation of liberty may look more like this:

Anecdotally, applications under s15 and s16 Mental Capacity Act from local authorities to the Court of Protection have also ‘spiked’ following the ruling in Neary, although I have not taken these into account. I reiterate: This is not taking into account the costs of managing authorities or the Official Solicitor; nor cases where a second public authority is a defendant, nor any damages payable for unlawful detention. And, as the number of appeals looks as if it is growing, the costs will do so also.

The rising costs of DoLS in the future?

If appeals continue to rise, and the costs of a Court of Protection cases relating to deprivation of liberty do not decrease, there are several possible outcomes:

- The cost to the public purse – to local authorities (and PCTs, until they are abolished), to the courts, to the Official Solicitor, the Ministry of Justice - may become intolerable.

- A single unanticipated hearing could easily have significant repercussions for a supervisory body’s budget. In response, supervisory bodies may seek ways to avoid authorisations and disputes coming to court; which may be incompatible with the Article 5 rights of detainees, and the Article 8 rights of detainees and their families.

- Likewise, the pressure on the Official Solicitor may lead to delays in DoLS cases and the other work of his office. One solution might be for other litigation friends to become available; recent case law suggests one option is to use paid representatives (AB v LCC (A Local Authority) [2011]). Their pay will also have to reflect the true amount of time of case management for a litigation friend; this will potentially add even more to the supervisory body’s costs. In wider terms however, their time is likely to be less expensive than the legally qualified case managers that work for the Official Solicitor.

- Although the interpretation of deprivation of liberty should not reflect the burden these cases place on the legal system, we must consider that there is a danger that this may still influence judicial reasoning. Certainly, many cases make reference to this issue, indicating at least that public authorities seem to view it as pertinent to the scope of Article 5 when presenting their case to the court.

It is of course possible that these costs are an overestimate; although I feel they are more likely to be overly conservative. It is also possible that costs will decrease in time, as case law becomes clearer and cases are dealt with in lower courts. However, my feeling is that the technical issues in the DoLS have not yet all been resolved. And I think, talking to DoLS teams, that cases like Neary may only be the tip of the iceberg in terms of disputes; we should expect more.

Futhermore, although the ruling in Cheshire in no small part attempted to simplify decisions around whether a deprivation of liberty is actually occurring, it may have opened up new debates around what is 'the appropriate comparator' for any given individual, and just how real does an alternative residence need to be to engage Article 5? Because so many safeguards and benefits attach to the scope of Article 5, I don't think we will see litigants letting this issue go so easily. Such is the complexity of disability, social care and people's lives, that determining issues on the basis of Cheshire is unlikely to be as simple as many lawyers seem to expect.

The ECtHR ruling in Stanev v Bulgaria today may also shift the ground on the meaning of deprivation of liberty, and is likely to result in more legal argument on this issue at the very least. In short, whilst I think it is possible that in the short term Cheshire will offer some means for supervisory bodies to avoid authorising DoLS applications, hence diminishing protections in the community, I don't think it will resolve the conundrum facing the legal system of how to deal with the ballooning costs of appeals.

This cannot be sustainable in the long term. In part the costs derive from having to seek authorisation and review for cases outside the scope of the DoLS; amending the framework to allow for authorisations in settings other than care homes and hospitals would certainly reduce the number of review cases. In part costs may be so high because the DoLS themselves are very complex (‘labyrinthine’, ‘byzantine’, ‘bureaucratic’), necessitating tortuous and protracted legal arguments.

To remedy this issue would require a total revision of the framework; and of course this would have significant attendant costs. Some disputes that could have been resolved earlier may be reaching court because of poor understanding and application of the DoLS (certainly, one hears anecdotally of many 'interesting' practices by DoLS teams). A revision of the code of practice to include important case law, or efforts by the Department of Health or CQC to disseminate more information on good practice, could perhaps stem some of these issues. And then, of course, are the perennial debates about whether DoLS appeals should be more like tribunals, or even held by tribunals, although my view is that nobody has yet conducted a proper analysis of why the cases are taking so much time, and what 'efficiencies' of approach could be found whilst still ensuring people's rights are upheld.

Another idea that I have been toying with would be to switch to a statutory definition of 'deprivation of liberty', which could be achieved by means of an amendment to the DoLS. Ideally this definition would be subject to public consultation so we could hear reasoned and evidenced arguments about who needs safeguards, rather than a mish-mash approach based on case law that is highly fact specific and problematic when applied to cases outside those facts.

Such a statutory definition would reduce the amount of time taken by public authorities and courts deliberating and debating the scope of Article 5, and potentially save considerably on legal argument (and hence, costs). It is possible that some cases engaging Article 5 could slip through this definition; but it is likely that they will with the present legal uncertainly anyway.

Furthermore, if the definition were given in regulations they could be relatively swiftly amended to take into account new Article 5 jurisprudence. If the scope of DoLS is determined centrally, rather than through case law, dissemination to managing authorities and supervisory bodies is also likely to be more robust. However if managing authorities and supervisory bodies are exploiting this uncertainty around the scope of the DoLS and under-applying the framework, it is possible that this lack of clarity works well for reducing budgetary pressures, if not for human rights and legal certainty.

Overall, I think if the argument that DoLS aren't 'fit for purpose' doesn't persuade the authorities that it's time to go back to the drawing board, then maybe the growing costs should persuade parliament that it would be prudent to engage in thorough post-legislative scrutiny. However, my concern is that high though these costs are, significant reforms would almost certainly cost more.

Instead what I suspect will happen is that the DoLS will continue to put a significant strain on the court system and public authorities, who will come under pressure to avoid using them wherever possible. I think it is possible that only a repeat of Bournewood, embarrassing litigation in Europe where the DoLS have failed to protect people's rights, will prompt serious revisions to the framework. With rulings like C v Blackburn with Darwen, we creep closer every day.

Lucy Series is a socio-legal researcher with interests in human rights law in the sphere of community care with a special focus on issues around mental capacity. Before starting her doctorate in law, she worked in a variety of different mental health and social care settings.

Official Solicitor reaches limit of resources for CoP healthcare and welfare cases

- Details

The Official Solicitor wrote to the President of the Court of Protection in December to inform him that he had reached the limit of his resources with regard to healthcare and welfare cases, it has emerged.

The Court of Protection team at 39 Essex Street, which revealed the existence of the letter in its monthly newsletter, described the development as of “very considerable significance for those concerned with health and welfare matters”.

The CoP team said: “As a result of this development, we understand that the Official Solicitor's position is that he is unable to accept invitations to act in any except the most urgent cases, namely serious medical treatment cases and section 21A appeals, other than those brought by the relevant person's representative. Section 21A appeals may be subject to a delay until a lawyer/case manager becomes available.

“All other cases, even where his acceptance criteria are met, are being placed on a waiting list. These cases will be accepted in accordance with the best estimate that can be given to their weighting and priority when a case manager becomes available to manage the case.”

The CoP team at 39 Essex Street said it also understood that this policy would remain in place until the volume of new cases reduced, or the Official Solicitor's resources for healthcare and welfare cases could be increased, or both, to enable him to revert to the previous acceptance policy.

Council faces JR over decision to axe funding of independent advice services

- Details

The London Borough of Newham faces judicial review proceedings over its decision to axe funding for independent advice services.

The case relates to the council’s plans – approved by its Mayor, Sir Robin Wales in November – to develop a new model for advice.

This model would see three tiers of service:

- Online self-help information, advice and guidance on debt, benefit and housing issues for residents able to self help;

- Direction from council officers, where required, in using the online self-help service;

- A one-to-one problem solving package advice service for residents where council officers “deal with immediate crises and work with clients to identify root causes of problems, address these problems and enable future self-help”. Access will be by referral only, from designated council services and external organisations.

The council hopes that its Information, Advice and Guidance (IAG) project will provide a more joined up method of delivery. The IAG project also has a savings target of £1m by the financial year 2012/13.

Between July 2008 and July 2011 Newham funded advice on social welfare law – including benefits, debt and housing – through a contract with Newham Advice Consortium. This funding amounted to £284,820 in 2010/11.

The grounds for the challenge include claims that Newham conducted a flawed consultation and was in breach of its duties under the Equality Act 2010.

The claimant’s lawyer, Pierce Glynn partner Gareth Mitchell, said: “Newham don’t seem to understand how important independent advice is to local people.

“The charities who were previously providing these services report that many very vulnerable people are no longer getting the help they need, including women who have experienced domestic violence, the elderly, and people from BME communities with high rates of social exclusion.”

Mitchell added: “Newham’s approach ignores all the research about how good independent advice prevents problems from spiralling out of control and costing taxpayers far more to resolve later down the road.”

Page 111 of 270