Artificial intelligence in Education and EHC Plans

Alice de Coverley and Jim Hirschmann analyse the opportunities and risks arising from the use of AI in education and education, health and care plans, and its impact on lawyers practising in the area.

- Details

Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) is revolutionising how lawyers work and the very nature of litigation. Each week we come across cases with at least some element of AI-generated content. This note considers how AI is already being used in education and by Local Authorities, what it might offer, and the risks it raises. It is written for lawyers, parents, local authority (“LA”) professionals, and others involved in education and EHCPs who wish to understand the direction of travel, and what it might mean in practical and legal terms.

Lawyers’ working lives have arguably been made easier: Lexis Nexis has launched its AI assistant, which provides a good way of finding starting points for legal research. Westlaw’s ‘Edge’ has improved its search functionality. At the same time, companies like Clearbrief are promising to change the way that court cases are prepared. There is no doubt that things are moving quickly.

Concerns remain, however, about ensuring that client data is adequately protected, that the nuance of human input is not lost and that the abilities of AI are not overestimated. Regulators around the world are already having to reprimand practitioners for sloppy overreliance on AI generation (see e.g CBC, B.C. lawyer reprimanded for citing fake cases invented by ChatGPT, 26 Feb 2024; The Guardian, High court tells UK lawyers to stop misuse of AI after fake case-law citations, 6 June 2025 (Judgment here)). LLM failures to reason, as documented in Apple’s June 2025 Illusion of Thinking paper, are also part of a much deeper problem.

But, like it or hate it, AI is here to stay, and Education Law is no exception. The Department for Education, in collaboration with the Chiltern Learning Trust and Chartered College of Teaching, have recently produced free support materials for use of AI in education. The materials are said to balance the need for staff and student safety with the opportunities AI creates. The Department for Education has also updated its overarching generative AI in education policy paper (as of 10 June 2025). At the end of June 2025, Ofsted released research and guidance around AI and how Ofsted will look at it during an inspection. Ofsted made clear: “The biggest risk is doing nothing”.

The EdTech Advisory Panel, meanwhile, has been focusing primarily on developing a potential AI Charter and Scorecard to support trust, transparency, and responsible scaling of AI in education. AI in Education has produced what it describes as a research-backed framework for responsible AI adoption for schools. AI Edify has published seminars, online courses, AI readiness audits and AI tools to equip educators to use AI responsibly and ethically.

Within the field of special educational needs, we are seeing the rise of potential AI applications that could genuinely support SEND provision. For instance, identifying opportunities for streamlining administrative processes around EHCPs, and the development of AI-assisted speech and language support activities. UCL’s ECHOES project, where Autistic pupils are able to explore and practice skills needed for successful social interaction using AI tools in a multimodal environment, is one example of many now emerging where AI is being used to support and enhance the lives of children with SEND.

Local Authorities are also looking to harness the power of AI in respect of Education Health and Care Plans (EHCPs). Two articles have caught our attention in the past few months:

- BBC, Council trialling AI for special needs reports, 23 May 2025 (Somerset Council is looking to see whether AI can be used to create basic EHCP reports. Somerset Parent Carers forum said that it had some concerns about how sensitive data would be shared but was willing to see the effectiveness of the trial).

- BBC, AI speeding up special educational needs reports, 12 May 2025 (Stoke-on Trent City Council appears to be in a position there “AI tools had been trained to extract information from documents such as psychological reports and write it into a plan - completing the task faster than a human.”)

The effort to use AI to improve EHCP provision specifically is not new. From December 2018-May 2019, prior to the widespread use of AI amongst the general population, Ealing, Staffordshire and Suffolk were granted £99k by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, to explore “Using Analytics and AI to aid the production of EHCPs”. The final project report concluded “We estimate cost and/or time savings of around 25%. That equates to annual savings of more than £60M nationally, and an average saving of £420k per Local Authority that adopts the technology”.

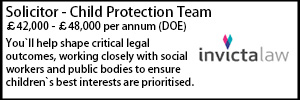

Some relatively well-developed options appear to have come to the market since, for instance Invision360, founded in 2021, claims that it “empowers local authorities with AI driven EHCP drafting and quality assurance modules. Founded by SEND expert Philip Stock, our solutions streamline complex processes, enabling organisations to work more efficiently and meet high standards for supporting vulnerable children and young people.” Similarly, the Agilisys EHCP Tool makes claims to save 6+ hours on each EHCP and that it “brings together insights from professional reports, analyses them using AI, and drafts personalised, high-quality EHC Plans - cutting down the time spent on manual writing and giving SEND teams more capacity to focus on children and families.”

We are also seeing the growth of parent-driven AI-powered SEND support bots, including SpektraBot, which describes itself as “a friendly, trauma-informed AI bot built to help families, schools, and young people navigate the SEND (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities) system. He explains things clearly, without jargon, and helps make sure you're not being fobbed off or left behind”.

What does all of this mean for lawyers? We suggest it means a few things.

First, optimising formats of evidence for tribunal

Even without Government reform on the horizon, there is likely to be a greater incentive to standardise EHCP formats nationwide and for expert reports to take a certain structure, as well as length, not only so that AI can be more uniformly applied but also so that it is easier to work out if AI has made a mistake.

Many of you will be aware of the “practice direction on procedure for the preparation of bundles in the special educational needs and disability and disability discrimination in schools jurisdictions of the health, education and social care chamber” that will apply to bundles being used in any Special Educational Needs or Disability Discrimination in Schools final hearings listed to take place after 15 July 2025. It is notable that paragraph [3] of that guidance stresses that it seeks to “achieve consistency in the preparation of hearing bundles in Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) appeals and Disability Discrimination (DD) in schools’ claims”.

While limiting page numbers appears to have the goal of making the bundle easier for humans, an ancillary benefit of greater consistency of bundling is that it should make it easier to produce effective AI tools which can enhance hearing preparation. Several experts, however, have raised concerns that the shortening of reports to please Tribunals impedes on their professional and ethical obligations towards the families of disabled children they are working for, particularly those who are complex.

Second, reducing hearing preparation time

While the tribunal process has not yet overtly embraced AI it seems to us that considerable time could be saved by refining bundles for hearings. AI tools could auto-generate hearing bundles that incorporate only the evidence relevant to the disputed areas of provision. It can also double-check that items are also not missing, when they had previously been served prior to the final evidence deadline. We know AI can already be used to generate parts of EHCPs so that the provision incorporated from documentation is automatically footnoted/hyperlinked.

Within a tribunal process, the working document stages could enable a relatively simple AI system to generate a report highlighting the evidence that is relevant to the dispute in hand and to enable a starting point for discussion or a reduced ‘essential reading list’. Focussed reading on areas of dispute could have the potential to reduce the reading time for Judges and lawyers and therefore the cost to clients engaged in EHCP litigation. It risks, however, nuance being missed. Output from generative AI is also highly susceptible to bias and misinformation. What AI produces will still need to be checked and cited appropriately by humans.

Third, improved evidence gathering

A centralised, as opposed to localised, database of schools, their location, up to date numbers, and the needs that they can typically meet might provide a way of identifying whether there are any placements, that are likely able to meet need and are sufficiently close to the child’s home but have not yet been consulted. Similarly, it may be possible to create a centralised database of relevant experts whose expertise can be sought by LAs in specific cases where they are not able to access NHS input quickly enough. In short, an effective AI tool could prompt human users to reflect on gaps in the evidence and ensure children’s needs are being promptly and fully understood. This, of course, would need to be balanced against properly handling sensitive information and having full regard to GDPR requirements.

Fourth, a greater scrutiny of LA process will be necessary

The risk of individuals on the ground fettering their discretion or not applying their mind to material evidence is real and may justify a challenge on public law grounds. We consider it inevitable that we will see challenges under public law where algorithms or AI tools are used to generate EHCPs without adequate human oversight, just as we saw in the great algorithm fiasco from Ofqual (something Alice de Coverley was involved in successfully litigating against in 2020).

Scrutiny of the way that local authorities apply AI is going to remain a live issue so long as new ways of working develop at pace. Guidance, such as that available for Civil Servants, about the importance of taking appropriate care and consideration with generative AI, may well be produced for LAs. Guidance for LAs will need to be reviewed far more regularly than other guidance, given rapid emerging practices, changing Government policy and our collective understanding of the use cases for this technology.

Final remarks

The requirement for an EHCP is usually due to evidence that a child needs a bespoke approach to meeting their needs. There is nuance and an EHCP is intended to capture a multitude of issues in the child or young person’s life. It is unlikely that AI will be able to make all the fine-tuned decisions that are required for an EHCP to accurately and fairly reflect a child or young person’s profile.

Keeping up with demand for EHCPs would ideally be achieved by further funding and research into more efficient approaches. In a climate where further funding is in short supply we should, however, welcome carefully introduced tools that can free up more human time and allow society to better ensure that children and young people have their needs met. Children must, however, be kept safe and their rights secured along the way.

We are all already being swept along by the current of AI change. Realising AI’s potential and pitfalls will require practitioners to keep up and engage with all the developments in this space.

Alice de Coverley and Jim Hirschmann are barristers at 3PB.