Nationally significant infrastructure projects, the EIA regime and propriety in decision-making

The High Court recently dismissed an EIA and apparent bias challenge to a development consent order relating to the UK’s largest port. Mark Westmoreland Smith KC and Armin Solimani explain why.

- Details

The High Court, by a decision of Mr Justice Saini, has dismissed a judicial review of the Secretary of State for Transport’s decision to grant the Associated British Ports (Immingham Eastern Ro-Ro Terminal) Development Consent Order 2024 (“the DCO”).

This was designated as a significant planning court claim, and raises important points concerning both the environmental impact assessment regime and propriety in planning decision-making, particularly in relation to Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects.

The DCO authorised the construction of a new “roll-on roll-off” berthing facility (“the IERRT”) at the Port of Immingham, the UK’s largest port by tonnage. The claim was brought by the operators of the adjacent Immingham Oil Terminal (“the Claimant”).

The central issues were (i) whether the SoS had conducted a flawed Environmental Impact Assessment by not assessing the navigational safety of a hypothetical large vessel using the IERRT and (ii) whether the SoS’s decision was tainted by apparent bias.

Both grounds were dismissed.

Ground 1 – Breach of IEIA Regulations

This ground of challenge contended that the Secretary of State, in various regards, had failed to properly consider the risk of a large vessel using the IERRT and colliding with the Claimant’s oil terminal, and the environmental impacts arising from that. This was said to be a breach of the Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 (“the IEIA Regulations”).

The Claimant argued that the environmental statement prepared by the Applicant, Associated British Ports (“ABP”) was unlawfully incomplete. It assessed the safety of numerous kinds of vessel using the facility, primarily by means of computer simulation of their navigation through the facility. But it was said to be defective in failing to assess the navigability of a hypothetical Design Vessel (“DV”). The DV is the largest vessel that could theoretically use the IERRT, given the 240m length of the IERRT’s berths.

Importantly, however, a vessel of the DV’s size does not currently exist in the real world, and key navigational characteristics of the DV, like its propulsion and manoeuvrability, remain unknown. The SoS therefore determined that she could not assess whether the DV could safely use the IERRT.

She instead relied on the fact that the various regulators of navigational safety in the Humber Estuary and the Port would scrutinise the DV, if and when it was created and sought to use the facility. These regulators, including the Humber Harbour Master and the Dock Master, were collectively referred to as forming a “river regime”.

This was an application of the principle in Gateshead MBC v Secretary of State for the Environment [1995] Env. L.R. 37, and the line of authorities following it. Essentially, the Gateshead principle holds that a planning decision-maker, when assessing the nature and acceptability of a development’s impacts, is entitled to have regard to the competent operation of existing regulatory regimes that deal with those impacts.

The Judge considered the SoS’ approach to be lawful and dismissed Ground 1, noting that it was a complaint about the substance of her judgment. He rejected the Claimant’s submissions that:

- The SoS was obliged, in the terms of the DCO, to restrict the use of the IERRT to vessels which had in fact been assessed, to comply with the Rochdale Envelope approach;

- That the Gateshead approach only applied to pollution control and not more widely; and

- That the Gateshead approach only applied to regulators with a specific statutory duty to control the impugned environmental effect.

Ground 2 – Apparent bias

The Claimants also argued that the Secretary of State who granted the DCO, the Right Honourable Louise Haigh MP, had acted in a way giving rise to an apparent bias.

There were two broad issues identified by the Claimant:

- Ms Haigh, while shadow Secretary of State (but one day after the general election had been announced) had visited the site for approximately 45 minutes and been given a tour of it by ABP management. The Claimant contended this was a ‘site visit’ relating to the DCO that should have included the objecting parties; and

- After becoming Secretary of State, Ms Haigh had briefly corresponded with ABP to exchange pleasantries, and had subsequently chosen to take the decision on the DCO herself and indeed approved it, which indicated a bias on her part.

The Judge applied the test in Porter v Magill [2002] 2 AC 357. The test is a two stage inquiry. First, the Court ascertains all the circumstances which have a bearing on the suggestion of bias. Then, the Court asks whether those circumstances would lead a fair-minded and informed observer to conclude that there was a real possibility that the decision-maker was biased.

Dismissing this ground, Saini J found the test was not made out on these facts. Ms Haigh visited the Port while in opposition and it was not in reality a site visit, as the Claimant contended. Her correspondence with ABP was generic and not indicative of a predisposition in their favour. She had also refused a dinner invitation from ABP while deciding their application. And it had been made clear at the tour that she may be required to determine the application so could not discuss it.

Mark Westmoreland Smith KC and Armin Solimani are barristers at Francis Taylor Building. They appeared for the successful Secretary of State, instructed by the Government Legal Department.

A copy of the judgment can be found here.

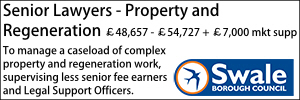

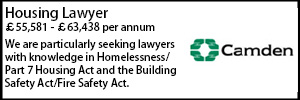

Lawyer - Property

Senior Lawyer - Contracts & Commercial

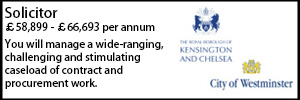

Trust Solicitor (Employment & Contract Law)

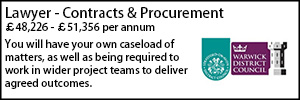

Contracts & Procurement Lawyer

Locums

Poll