Environmental enforcement powers: Walker v Chelmsford City Council [2020] EWHC 635 revisited

Dr Dan Jacklin examines the current state of play in Environmental Law after the Walker decision of 2020 - including potential complications and unforeseen consequences.

- Details

Following Walker v Chelmsford City Council [2020] EWHC 635 (Admin), the present position is that the s.108(4)(j) power under the Environment Act 1995 does not entitle an authorised person to require a person to answer written questions and provide written answers. Under the power is s.108(4)(j), the questions must be asked orally whilst in-person and on the premises.

In 2020, our now Head of Regulatory, Ben Mills, produced an article evaluating the merits of the Walker decision which can be read here. The Five years on, this case continues to generate questions in work for local authority clients. In this article, Dr Dan Jacklin considers whether the decision gives rise to a number of potential complications and unforeseen consequences which both enforcement bodies and defendants may have to consider with care.

Some of those considerations, include:

- The court was not required to give judgment on the scope of s.108(4)(j) in order to resolve the issues before it, but chose to give judgment on the issue in any event. Whether the comments were obiter is a key question;

- The decision failed to acknowledge that an authorised person may be authorised to exercise one or more of the powers in s.108(4) (see the use of the words “any of the powers” in s.108(1); it is not incumbent for them to be authorised to exercise all of the powers in that section. That appears to be a strong indicator that each power in s.108(4) was intended to be self-contained;

- As acknowledged by Laing J in the judgment, there is nothing expressly written into the wording of s.108(4)(c) which suggests it is contingent on the exercise of the powers under s.108(4)(a) (power of entry) or (b) (power to take other persons, equipment and materials). Considering the significance of the power’s scope, that is a surprising omission;

- “Premises” is defined by the EA 1995 as “includes any land, vehicle, vessel or mobile plant”. The definition is so wide, it is difficult to conceive of a place a defendant could be where an authorised person would not have the right to enter to find him there and compel him to answer oral questions. The only type of premises where an authorised person is restricted in any way from entering premises is when it concerns “residential premises”, which requires either consent of the occupier or a warrant (s.108(6), EA 1995);

- Notwithstanding that consent is not required to enter premises using the s.108(4) powers (see Millmore and Ors v Environment Agency [2019] EWHC 443 (Admin) at [11]), an authorised person may enter a site by consent as s.108(6) makes this clear in the context of residential premises. Where an authorised person has entered a site by consent, the authorised person has not exercised a power of entry under s.108(4)(a). Applying the ratio of Laing J in Walker, this would lead to the wholly unsatisfactory position where, if an occupier gives consent to enter the premises, the authorised person would be unable to exercise s.108(4)(j) power to require answers to questions orally whilst in person on the premises;

- As considered at paragraph [15] of Millmore, some premises entered using the s.108(4)(a) power are unoccupied. Laing J’s interpretation of the s.108(4)(j) power as being restricted to questioning in person and on the premises means that a defendant can easily evade answering any questions by simply not being present at the premises or moving from one residential premises to an adjacent residential premises. It is difficult to consider that Parliament intended to restrict the use of the s.108(4)(j) power in this way;

- If s.108(4)(c) is contingent on s.108(4)(a) and (b), as Laing J finds in Walker at paragraph [23]-[25], then an authorised person would have no power to “make such examination and investigation” as was necessary before exercising a power of entry;

- At paragraph [15] of Walker, Laing J acknowledges that both s.108(4)(l) is not contingent on having exercised of a right of entry but does not proceed to examine how that section interacts with s.108(4)(j). If information is “necessary” (s.108(4)(l)) for the authorised person to “investigate” (s.108(4)(c)) whether “pollution control or flood risk enactments are being complied with” (s.108(1)) then surely providing “such assistance with respect to any matters or things within that person’s control or in relation to which that person has responsibilities” (s.108(4)(l)) would require a person to provide such information, including if that meant answering written questions in writing?

Effect on practise

Notwithstanding that an authorised officer appears, at least whilst Walker remains good law, to restrict the power to require answers to questions to only those asked orally in person, there is nothing preventing an officer seeking written answers to written questions by consent.

Both the answers given voluntarily in writing and compelled under s.108(4)(j) are admissible for use in criminal proceedings against persons other than the giver of those answers, such as their employer or a colleague.

In effect, written answers to written questions are being volunteered by consent rather than compelled under s.108(2)(j), but that consent is given against a backdrop that authorised persons can subsequently go to premises where a person is located and compel answers in person if written answers are not provided (that, of course, relies on the prosecution being able to locate the suspect). Many defendants prefer giving written answers, as it gives them time to work with their legal team to better formulate the answers provided.

To some extent, this outcome is unsurprising. It has long been a norm in principle-based regulatory systems that duties specify the desirable end, in this case, the authorised person receiving the information they need to prosecute environmental crime and prevent further environmental harm, but also respect a defendant’s right to decide the means by which they seek to achieve that end.

The benefits of having greater legal input into written answers will need to be weighed up against the fact that answers, if they meet the criteria set out in s.9 of the Criminal Justice Act 1967 (‘1967 Act’), were volunteered rather than compelled under s.108(4)(j), so will be admissible; as the s.108(12) prohibition of the admissibility of answers compelled under s.108(4)(j) will not apply.

Notably for Defendant practitioners, where answers are volunteered rather than compelled under s.108(4)(j), the authorised officer cannot compel the attachment of a statement of truth to the answers given. The evidence will not be admissible under s.9(2) of the 1967 Act without such a statement being attached.

Offering answers without a statement of truth risks an authorised person simply falling back on their s.108(4)(j) power. The risk for Defendants is that providing answers accompanied by a statement of truth will likely make the answers admissible under s.9(2) of the 1967 Act.

Defendants, therefore, have a real dilemma on their hands. Answer the questions orally in person and utilise the protection in s.108(12) to prevent those answers being admissible in any proceedings. Alternatively, take the time to prepare written answers better supported by legal representatives, but know that such answers will likely need to be accompanied by a statement of truth and will likely then be admissible in any subsequent proceedings against them.

Contrary to Laing J’s concern at having weakened the investigative powers of authorised persons, the opposite is true, because whereas before written answers to written questions would have fallen under s.108(4)(j) and had the protection of s.108(12), they are now without such protection.

Perhaps the most significant outstanding question is as regards the scope of “assistance” under s.108(4)(l). “Assistance” is not defined by the EA 1995. It is notable that s.110(2) uses both “assistance” and “information” in the same sentence, implying there is a material difference between the terms. This is particularly pertinent as failing or refusing to provide “assistance” is an offence under s.110(2) (see Milmore [38]-[40]).

Closing remarks

Section 108(4) is ripe for further guidance from the appellate courts should a suitable test case bring such matters into issue. Until such guidance is issued, the differing practises of local authorities is likely to foster amongst Defendants greater dependence on their legal advisers.

Dr Dan Jacklin is a barrister at St Philips Chambers.

Whilst every effort has been taken to ensure that the law in this article is correct, it is intended to give a general overview of the law for educational and/or informational purposes. It is not intended to be a substitute for specific legal advice and should not be relied upon for this purpose.

This article represents the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the view of any other member of St Philips Chambers.

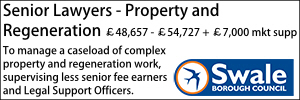

Lawyer - Property

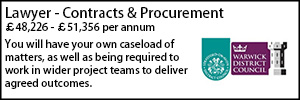

Contracts & Procurement Lawyer

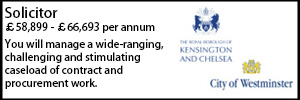

Trust Solicitor (Employment & Contract Law)

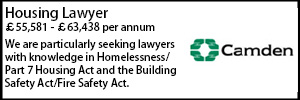

Senior Lawyer - Contracts & Commercial

Locums

Poll