Developer fails in High Court challenge to condition preventing occupation of approved dwellings until water neutrality demonstrated

The High Court has dismissed both grounds argued by a developer in a planning appeal over a condition concerning water use neutrality.

- Details

Mrs Justice Lang rejected submissions from Crest Nicholson Operations that both the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government and Horsham District Council had been wrong to impose a planning condition on a development of 280 homes in Faygate that prevented them being occupied until water neutrality was demonstrated.

The court heard that part of Horsham’s water supply is abstracted from the River Arun, near a group of nature conservation sites designated for rare and protected habitats.

Horsham originally handled the planning application but it was recovered for the Secretary of State’s determination because it involved a residential development of more than 150 units, which the judge noted would significantly affect the Government's objective to secure a better balance between housing demand and supply.

The inspector concerned recommended approval of the reserved matters, subject to Condition 6, the condition concerning water neutrality.

He concluded this was necessary to ensure compliance with regulations 63(5) and 70(3) of the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, until such time as access into the council’s water offsetting scheme or an equivalent scheme has been secured.

Crest Nicholson submitted that the imposition of Condition 6 was unlawful on two grounds.

The first was that the inspector and the Secretary of State erred in law and acted irrationally by proceeding on the basis that groundwater abstraction might continue at a level that could not be excluded from resulting in harm to protected habitats, by reliance on “imperative reasons of overriding public interest” under regulation 64(1) of the Habitats Regulations.

Crest Nicholson’s second ground was that the inspector and the Secretary of State erred in their approach to the effect of uncertainty in the appropriate assessment under the Habitats Regulations.

It said the Environment Agency and Southern Water could be expected to fulfil their legal obligations under the Habitats Regulations and what was required was certainty as to the end, not the means.

Natural England had advised that development within the affected area should not add to the impact on water supplies, with water neutrality defined as when the use of water before the development is the same or lower after the development is in place.

Examining Crest Nicholson’s first ground concerning levels of abstraction, Lang J found: “In my judgment, there is no basis in these passages of the [inspector’s] report to suggest that the inspector misdirected himself on regulation 64 of the Habitats Regulations and the imperative reasons of overriding public interest test…

“An expert decision-maker can be taken to be familiar with the relevant statutory framework and legal principles, in the absence of a ‘sufficient positive contra-indication’”.

She said the inspector’s report was correct and had found the evidence was insufficiently certain to determine whether or not this test could apply.

Lang J concluded: “I accept the [Secretary of State’s] submissions that the inspector did not misdirect himself in law. Furthermore, his findings, based on the evidence before him, were a lawful exercise of his planning judgment, and cannot be characterised as irrational.”

Crest Nicholson’s second ground was that the inspector erred in his approach to how much freedom of action the Environment Agency had while still in accord with its obligations under the Habitats Regulations.

Lang J said: “On my reading of the report, I consider that the inspector had the relevant provisions of the Habitats Regulations (regulations 9(3) and 63) well in mind when considering the position of the EA:

“It is also clear from [various] paragraphs that the Inspector was looking ahead to the EA’s exercise of powers under section 52 WRA 1991, at which point regulation 63 of the Habitats Regulations would be engaged.”

She rejected as “misconceived” Crest Nicholson’s submission that the inspector and the Secretary of State erred in finding that the unspecified future actions by the EA and/or Southern Water did not provide evidence of reasonable certainty that no adverse effects on the integrity of the Arun Valley sites would result from the proposed development.

The judge explained: “The proposition that a planning decision-maker is entitled to proceed on the basis that other regimes will operate effectively and properly is not a legal requirement to do so.

“It is a rebuttable presumption that a decision-maker may depart from, if the evidence justifies it. Whether or not to do so is an evaluative public law judgment for the decision-maker, subject only to challenge on Wednesbury grounds.”

There had been specific advice from Natural England that abstraction was having a detrimental impact on the protected sites and therefore further development should be avoided unless it was subject to water neutrality mechanisms, and this had been accepted by the Environment Agency, Southern Water and Horsham.

Lang J said: “The inspector properly explored the uncertainty in the evidence base and its consequences before concluding that it could not be ascertained with reasonable certainty that the proposal will not adversely affect the integrity of the Arun Valley sites.

“No public law error is disclosed in the carefully reasoned conclusions by the inspector and the [Secretary of State] that, in their judgment, reliance upon other regulatory regimes lacked the necessary degree of certainty to reach the high standards required of the Habitats Regulations.”

She concluded it was not irrational or otherwise unlawful for either of them to decide there was insufficient certainty to conclude a positive appropriate assessment without Condition 6 and this was “well within the scope” of planning judgment.

Mark Smulian

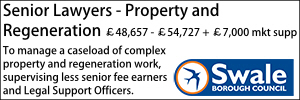

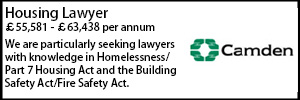

Lawyer - Property

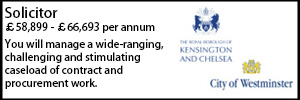

Senior Lawyer - Contracts & Commercial

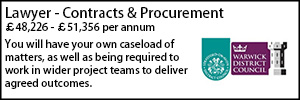

Contracts & Procurement Lawyer

Trust Solicitor (Employment & Contract Law)

Locums

Poll