Into the breach

Local authorities have a real opportunity to show community leadership by filling the funding gap, argues Mike Mousdale.

When we talk about local authorities and banks in the same sentence, it is usually a bad news story. Most recently it was the Icelandic banks episode, but those with longer memories, especially local government lawyers, will only ever associate Credit Suisse with landmark case law in which local government got a bit of a kicking.

What all of that teaches local authorities is that they need to be cautious in their dealings with the banks. But currently, it is the banks that are being cautious and it is the local authority and its community which is feeling the effect. Whilst local authorities still have the ability to borrow without too much difficulty from the Public Works Loan Board, the private sector is having a lot more difficulty in getting the banks to part with their cash. As much of the current local government agenda is dependent upon private sector investment, this is not good news. For examples, deal flow in PFI is down to a trickle, regeneration developments are stalled and the local economy’s supply of credit is dried up.

Maybe the time has come for the tables to be turned. Rather than wait for the banks to shake off their inertia, local government can pick up the mantle and fill the funding gap itself. Not by throwing scarce capital resources at the problem, but by taking up the role of lender. Not only will it get things moving, but it will make a return on its investment, too. All to the benefit of the council taxpayer. If ever there was a time to show community leadership and get the local community working again, it is now.

So that stalled PFI deal can be moved by the authority filling the funding gap, not by capital contribution, but by lending pari passu with commercial banks and institutions like the European Investment Bank and the Treasury Infrastructure Fund. That embarrassing hole in the ground with planning permission for commercial development in the town centre can be kick-started with investment from the local authority, which has a vested interest in seeing the proper planning of its area achieved and the development secured to bring in jobs to the local economy.

The small and medium enterprise, especially one which is part of the council’s supply chain, which is otherwise financially sound, but simply cannot get credit to invest in assets and equipment, can be provided with a facility or loan, which thereby not only delivers economic well-being to the area but might secure continuity of service and supply to the council in a key functional area.

Wait a minute though. One thing our dealings with the banks in the past taught us is that local government has to operate within its powers and some of this looks to be right at the margins. And everyone is a little bit windy on the powers front at present post-LAML. So are we OK legally?

Well in our view, in principle, yes. Undoubtedly, LAML was an attack on the application of well-being, but we should not now park section 2 on the shelf and quietly forget about it. Many of the actions of the type described here are palpably for the wellbeing of the Council’s area. As the ODPM/DCLG Guidance on the use of well-being observes, in explanation of section 2(4) (which sets out possible uses of the power, including, incurring expenditure, financial assistance and the entering into arrangements or agreements with any person): “such financial assistance can be given by any means authorities consider appropriate, including by way of grants or loans (our emphasis)…”.

But local authorities need not just rely on well-being. Section 12 of the Local Government Act 2003 gives the power to invest for any purpose relevant to its functions under any enactment.

But care and caution is needed. Such assistance could amount to state aid, depending upon its purpose and the interest rates charged. This is a complex issue, which an authority should always take specialist advice upon. And then of course, there is always the other limb of the ultra vires doctrine – exercise. At the very least, we would expect a council to act prudently and commercially. No lender would lend without doing appropriate due diligence on the borrower and the purpose of the loan. The council probably should not forego an arrangement fee and the borrower should pay the council’s legal fees. It should take appropriate security for the loan. This is what a bank would do and the council should not act any differently. councils should not get into the business of lending to undercut banks or to be a soft option for the local borrower.

In our view, this is something that councils can be doing, to fill what is hoped will be a temporary blockage in the commercial lending market. It is what local government does best – to be there for the community in times of crisis and difficulties. This is not part of the wider discussions about general powers of competence, which ought not deflect councils from recognising what powers they already have and how they can be used for the benefit of their communities. As ever, the local authority lawyer should be at the forefront of making these solutions work and ensuring that the council exercises its powers correctly.

Mike Mousdale is a partner at Eversheds.

This article first appeared in Public Finance magazine on 30 October 2009.

- Details

Local authorities have a real opportunity to show community leadership by filling the funding gap, argues Mike Mousdale.

When we talk about local authorities and banks in the same sentence, it is usually a bad news story. Most recently it was the Icelandic banks episode, but those with longer memories, especially local government lawyers, will only ever associate Credit Suisse with landmark case law in which local government got a bit of a kicking.

What all of that teaches local authorities is that they need to be cautious in their dealings with the banks. But currently, it is the banks that are being cautious and it is the local authority and its community which is feeling the effect. Whilst local authorities still have the ability to borrow without too much difficulty from the Public Works Loan Board, the private sector is having a lot more difficulty in getting the banks to part with their cash. As much of the current local government agenda is dependent upon private sector investment, this is not good news. For examples, deal flow in PFI is down to a trickle, regeneration developments are stalled and the local economy’s supply of credit is dried up.

Maybe the time has come for the tables to be turned. Rather than wait for the banks to shake off their inertia, local government can pick up the mantle and fill the funding gap itself. Not by throwing scarce capital resources at the problem, but by taking up the role of lender. Not only will it get things moving, but it will make a return on its investment, too. All to the benefit of the council taxpayer. If ever there was a time to show community leadership and get the local community working again, it is now.

So that stalled PFI deal can be moved by the authority filling the funding gap, not by capital contribution, but by lending pari passu with commercial banks and institutions like the European Investment Bank and the Treasury Infrastructure Fund. That embarrassing hole in the ground with planning permission for commercial development in the town centre can be kick-started with investment from the local authority, which has a vested interest in seeing the proper planning of its area achieved and the development secured to bring in jobs to the local economy.

The small and medium enterprise, especially one which is part of the council’s supply chain, which is otherwise financially sound, but simply cannot get credit to invest in assets and equipment, can be provided with a facility or loan, which thereby not only delivers economic well-being to the area but might secure continuity of service and supply to the council in a key functional area.

Wait a minute though. One thing our dealings with the banks in the past taught us is that local government has to operate within its powers and some of this looks to be right at the margins. And everyone is a little bit windy on the powers front at present post-LAML. So are we OK legally?

Well in our view, in principle, yes. Undoubtedly, LAML was an attack on the application of well-being, but we should not now park section 2 on the shelf and quietly forget about it. Many of the actions of the type described here are palpably for the wellbeing of the Council’s area. As the ODPM/DCLG Guidance on the use of well-being observes, in explanation of section 2(4) (which sets out possible uses of the power, including, incurring expenditure, financial assistance and the entering into arrangements or agreements with any person): “such financial assistance can be given by any means authorities consider appropriate, including by way of grants or loans (our emphasis)…”.

But local authorities need not just rely on well-being. Section 12 of the Local Government Act 2003 gives the power to invest for any purpose relevant to its functions under any enactment.

But care and caution is needed. Such assistance could amount to state aid, depending upon its purpose and the interest rates charged. This is a complex issue, which an authority should always take specialist advice upon. And then of course, there is always the other limb of the ultra vires doctrine – exercise. At the very least, we would expect a council to act prudently and commercially. No lender would lend without doing appropriate due diligence on the borrower and the purpose of the loan. The council probably should not forego an arrangement fee and the borrower should pay the council’s legal fees. It should take appropriate security for the loan. This is what a bank would do and the council should not act any differently. councils should not get into the business of lending to undercut banks or to be a soft option for the local borrower.

In our view, this is something that councils can be doing, to fill what is hoped will be a temporary blockage in the commercial lending market. It is what local government does best – to be there for the community in times of crisis and difficulties. This is not part of the wider discussions about general powers of competence, which ought not deflect councils from recognising what powers they already have and how they can be used for the benefit of their communities. As ever, the local authority lawyer should be at the forefront of making these solutions work and ensuring that the council exercises its powers correctly.

Mike Mousdale is a partner at Eversheds.

This article first appeared in Public Finance magazine on 30 October 2009.

Senior Lawyer - Contracts & Commercial

Trust Solicitor (Employment & Contract Law)

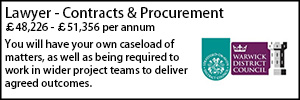

Contracts & Procurement Lawyer

Lawyer - Property

Locums

Poll